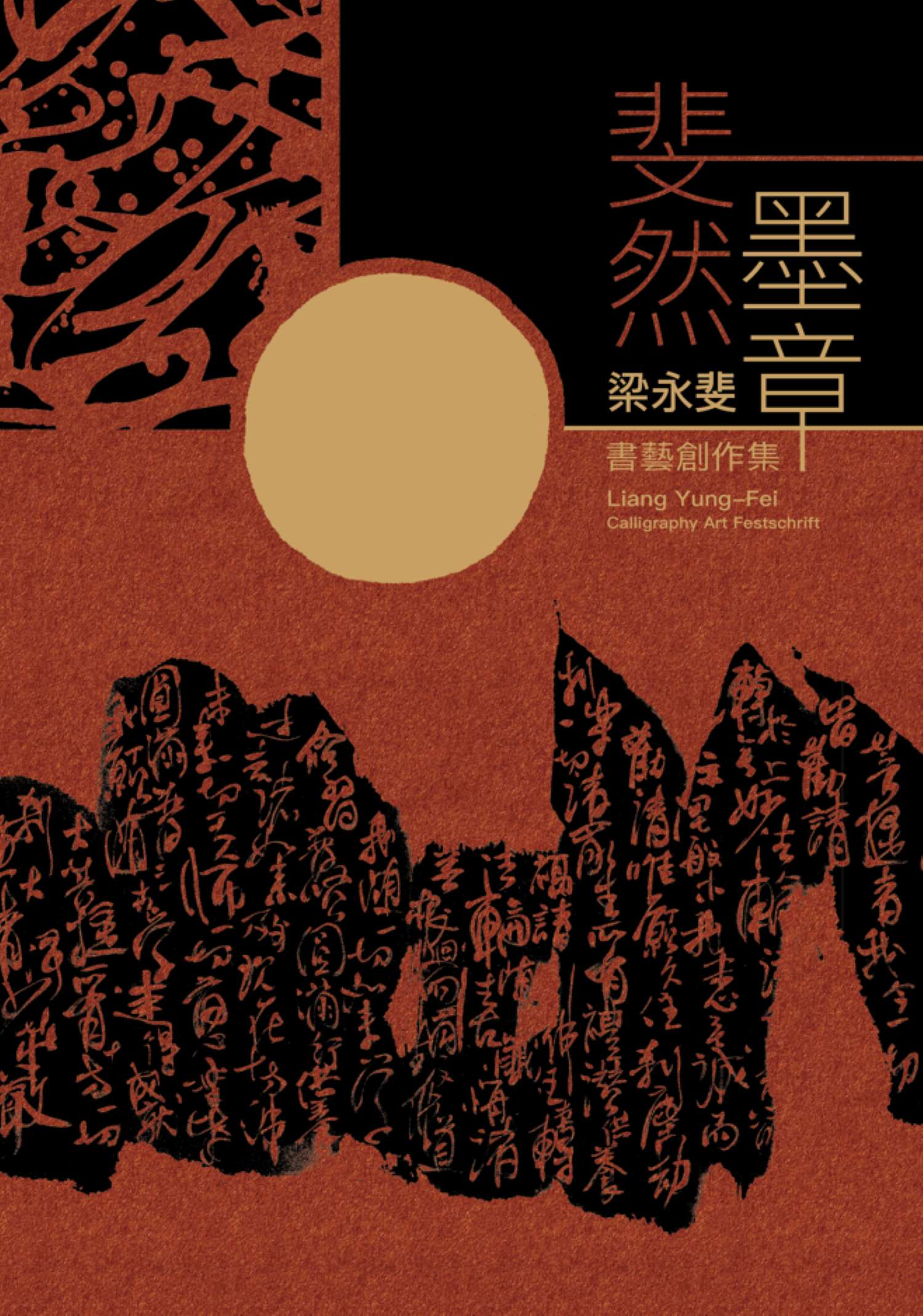

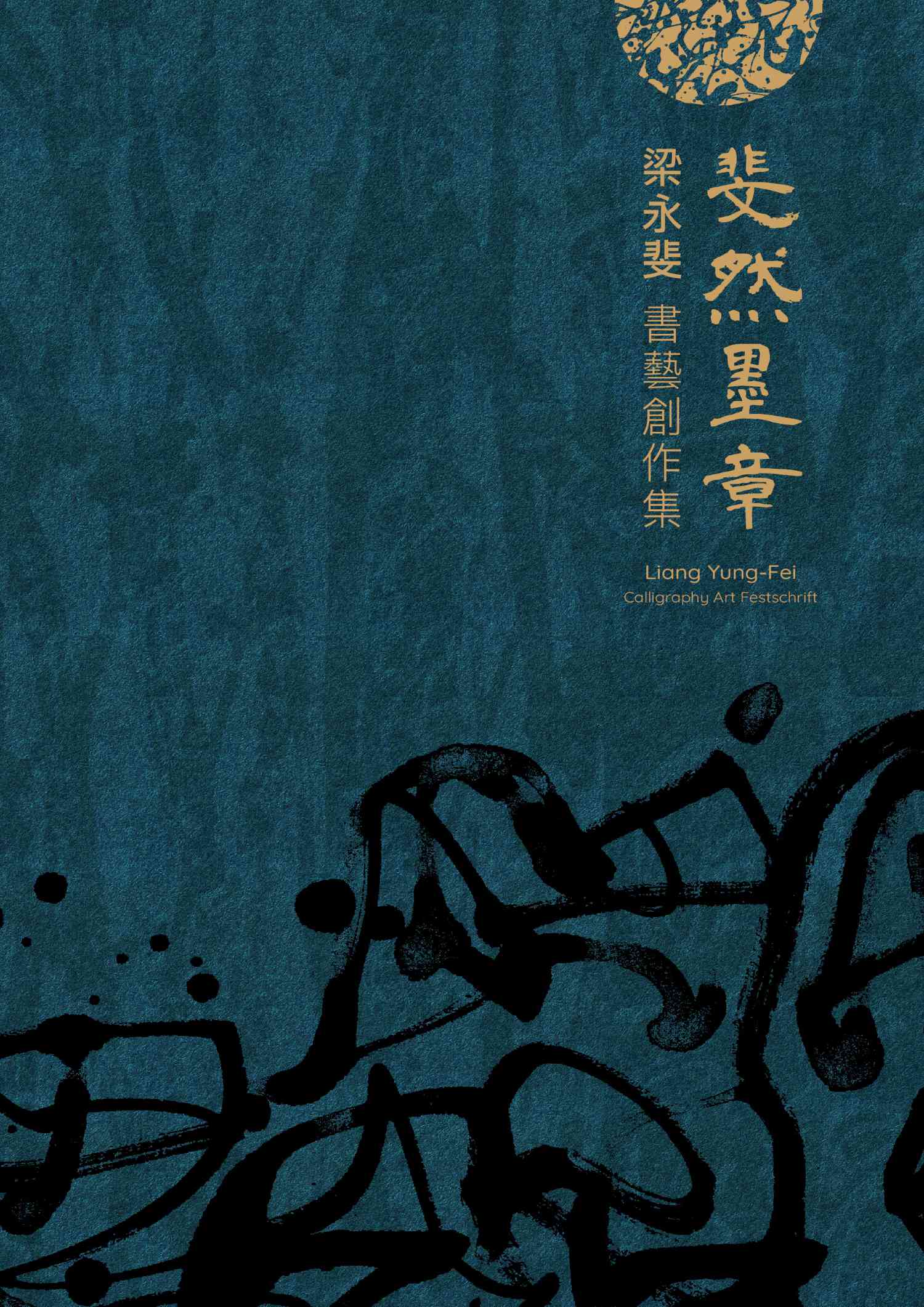

《Brilliant Ink – Liang Yung-fei Calligraphy Art 》

The evolution of Chinese characters first began from inscriptions carved out by knives. A brush has its limitations in fully expressing the spirit of calligraphic art. There must be power, speed and emotion, and the power comes from pressing the knife against the surface it is carving. Yung-fei’s calligraphy embodies the power of knife carving, ancient styles, and pictography. His words are self-contained, intriguing but not strange, while effortlessly striking a fine balance between conventional and radical. They fully encapsulate the original spirit of calligraphy, and are full of pictographic twists and turns, so his calligraphy is far more pictorial than the formal sense of writing. The greatest magic of calligraphy is that it does not use the content of the words to communicate with the audience, but the abundant power and emotion of the writer to move the viewer.

Calligraphic art should be wild but not chaotic. The difference between wildness and chaos is that the former is beautiful, and the latter is not. In art creation, beauty is derived from sensibility, and sensibility must be nurtured by rationality for such works to be attractive. Yung-fei’s lines are not subject to any limiting formal frameworks, but have a strong sense of musical rhythm. First-time viewers of his work might find it hard to know where to begin and where it ends, but if you observe long enough, you will find that there are actually numerous starting points, and no matter where the viewer starts, it will take you on your own tour through the painting ‘to see, to play and to stay’. There are many contemporary artists who create messy paintings today, but noise will never become music, and music is not rigid, but full of various forms, gestures, and states. At present, there are many avant-garde artists, but those whose art has reached the realm of music rather than just mere noise, are extremely rare.

In this book, Yung-fei’s works is divided into five different series, which include a total of 100 pieces of his works from different creative phases and styles.

Exhibition Series

Writing a Forest – Creating Forests with Characters

In Eastern writing traditions, writing is mostly done from top to bottom. Whether it is written on paper or carved on stone stele, rows of characters line up to form a forest of words. Thus, since ancient times, there has been metaphors that compare words and steles to forests. In this series of works however, Yung-fei grasps the essence of “forest of words” but is not restricted by its form and format. Using different perspectives of observing the woods as a guide for composition, he gives full play to the structural characteristics of different scripts, making bold changes to the lines, and then superimposing them with dots, lines, and patches of coloured ink to create multi-layered effects, using the wet-on-wet method to create a variety of “literary forests” such as towering pine and plum blossom forests in full bloom. The lines in the pictures are smooth and unrestrained, free, and wild. Through the changes between light and heavy, fast, and slow, dry and wet ink strokes, as well as well-structured colours, shades and contrast, the artist immerses the viewers in a strong visual experience of being in a forest of words. One can feel the soft touch of a light breeze blowing your face gently and even hear the rustling of the leaves. In addition, the symbolic elements of the Sun and the Moon often appear in this series, creating an atmosphere of “being in the forest and watching the moon”. The unique perspective, method, and technique of this series of “trees” show that the artist intends to blur the boundaries of different art forms to achieve the integration of calligraphy and painting.

Writing the shape – Introducing New Dimensions to the Clerical Script

The clerical script is horizontally long and vertically short. Its wide and flat shape is as stable as Mount Tai, but it also pays attention to brushwork such as “silkworm head and goose tail” and “one wave with three twists and turns”, adding elegance to this otherwise thick shape. In this series, Yung-fei further modifies the characteristics of the clerical script. Whether it is reducing the spaces between the strokes to an almost “airtight” level, or mixing it with semi-cursive and cursive scripts in the same text, he experiments to discover the painterliness of the lines by deconstructing the layout of Chinese characters, hence creating his own artistic style.

Writing the Form – Both Calligraphy as well as Painting

The history of calligraphic art is long and complicated. A brush, a stick of ink, a piece of paper, and an inkstone now carry profound cultural and artistic connotations after thousands of years. When writing calligraphy, there are rules to follow, as the primary purpose of words is to convey meanings. Through thousands of years of development, rules for writing such as how to use the brush, how to structure the characters, how to compose an article as well as aesthetic standards for different scripts were established and characterized, these form the norms in calligraphy. Therefore, since ancient times, calligraphers have established the habit of copying ancient copybooks and inscriptions of different scripts to learn and improve. Yung-fei is no exception. When he was young, his interest in calligraphy was inspired and nurtured by his uncle Mr. Liang Zhao-jin. After that, he continued to learn from Ouyang Xun’s regular script, Huang Shangu’s unrestrained style, Mi Fu, Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi’s cursive brushwork, Zhang Qian Stele, Wu Changshuo’s seal script and bronze script from Western Zhou Dynasty, mastering the essence of different scripts, such as regular,clerical, semi-cursive, seal, and cursive scripts, and thereby laying a solid foundation for calligraphy art creation.

Writing without Boundaries – A Sonata Fusing the East and the West

This series uses the bronze script from the Western Zhou Dynasty as the main element, experimenting with different combinations of one or more characters to create a strong artistic expression. Playing with the thickness, length, straightness, and smoothness of the lines to construct a multi-dimensional sense of space, it is a modern representation deeply rooted in tradition. The use of the three primary colours[1] of cyan, magenta, and yellow coloured in the blank spaces of different shapes is carefully thought out to create a sense of painterliness and rhythm, which pay tribute to the works of Western artists, like Miró and Mondrian. After going through a phase of breakthroughs and pictorialization, Yung-fei’s calligraphy is like a butterfly emerging from the cocoon, gradually developing his own unique style, while enjoying and never tires of the process of stylistic metamorphosis.

Writing in Celebration – Fruits of Love

The fruits stacked up in this series of works resemble cherries as well as oranges, and are bright red and full. The calligraphic lines are like vines, wandering among the perfectly ripe and plump fruits, sometimes tight and sometimes loose. At times, the fruit is the focal point of the picture, while sometimes it is only decorative. The overall arrangement is well-proportioned, and the atmosphere is filled with the joy of the harvest, as well as a sense of Zen-like calmness after harvesting a year’s hard work.Collection of Tang Poems, “There are endless beautiful things between the Heaven and the Earth, but only the ones with true wisdom can see and enjoy them.” Yung-fei coalesces his farming experience, folk traditions, and Buddhist teachings, to create rich and touching works that embody a deep respect and gratitude for all beings in the world.